When you were a kid, your mother may have reminded you to always drink your milk. But these days many adults find themselves experiencing some degree of what’s known as lactose intolerance.

Lactose is a sugar found in dairy products. When you consume food or drink containing lactose, an enzyme in the small intestine called lactase helps you digest the sugar. But when you’re lactose intolerant, you can’t digest these sugars, and this creates excess gas and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

The most common type of lactose intolerance is primary lactose intolerance. In primary lactose intolerance, you’re born with a normal amount of lactase. But by the time you reach adolescence or adulthood, your lactase production decreases sharply, and it becomes very difficult to digest foods that contain dairy. (You may hear this described as lactose nonpersistence.)

Secondary or acquired lactase deficiency arises when an infection or disease — such as celiac disease, gastroenteritis, or Crohn's disease — damages the small intestine.

Congenital lactase deficiency is a rare inherited disorder in which the small intestine produces little to no lactase from birth. (More on that below.)

Here’s everything you need to know about lactose intolerance — and what to do about it.

Causes and Risk Factors of Lactose Intolerance

Many people with lactose intolerance have a deficiency of the enzyme lactase because their small intestine doesn’t produce enough lactase. (The medical term for this state is hypolactasia.)

This deficiency may lead to lactose malabsorption, in which undigested lactose makes its way into the large intestine and colon. There, bacteria break it down, resulting in increased gas and fluid in the colon (and unpleasant bloating, flatulence, and other tummy symptoms).

Risk factors for lactose intolerance include:

- Age (it tends to appear after adolescence or young adulthood)

- A person’s race or ethnicity

- Premature birth

- Chemotherapy or radiation treatments for cancer

Duration of Lactose Intolerance

There's no cure for lactose intolerance, but most people are able to control their symptoms by making changes to their diet.

Complications of Lactose Intolerance

BIPOC and Lactose Intolerance

Resources We Love

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’s Eat Right website offers a wealth of clear and helpful information on how and what to eat when you’re lactose intolerant.

Additional reporting by Joseph Bennington-Castro.

Editorial Sources and Fact-Checking

- Malik T, Panuganti K. Lactose Intolerance. StatPearls. June 26, 2020.

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition for Lactose Intolerance. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. February 2018.

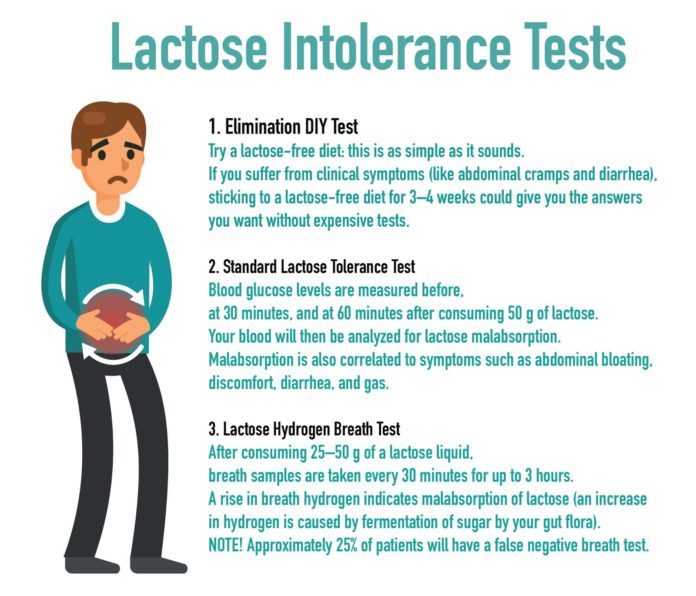

- Diagnosis of Lactose Intolerance. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. February 2018.

- Swagerty D, Walling A, Klein R. Lactose Intolerance. American Family Physician. May 2002.

- Lactose Intolerance. MedlinePlus. August 18, 2020.

- Vitamin D. National Institutes of Health. October 9, 2020.

- Storhaug CL, Fosse SK, Fadnes L. Country, Regional, and Global Estimates for Lactose Malabsorption in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology. October 2017.

- Lactose Intolerance. Harvard Health Publishing. January 2019.

- Lactose Intolerance. Mayo Clinic. April 7, 2020.

- Lactose Intolerance. Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- Definition and Facts for Lactose Intolerance. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. February 2018.