Zika is a virus that is mainly spread by the bite of an infected mosquito, though other routes of infection are possible.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has an up-to-date world map showing areas with active Zika transmission.

Causes and Risk Factors of Zika Virus Infection

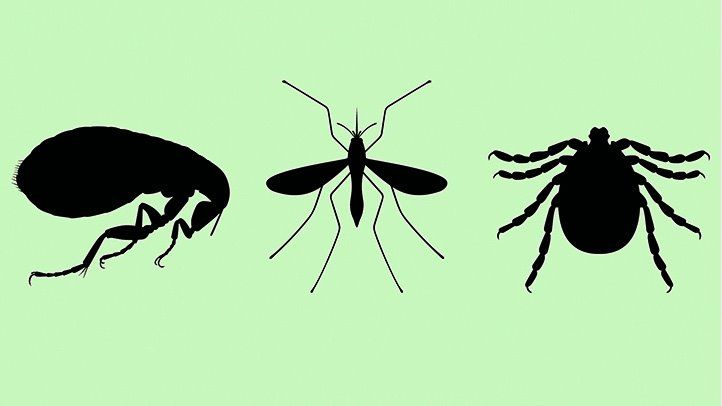

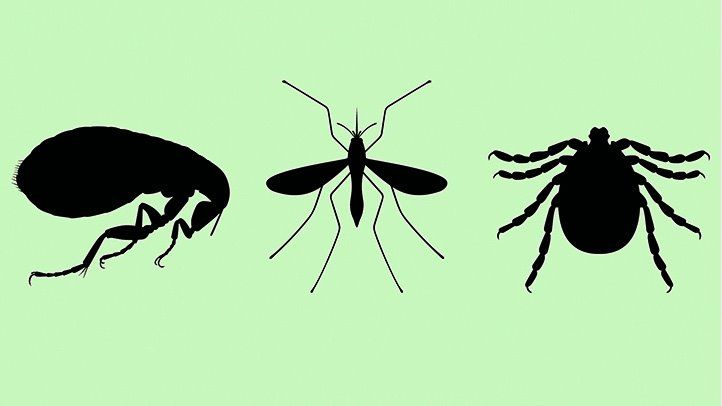

The Zika virus is spread primarily through the bites of infected Aedes mosquitoes (including the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus species).

The mosquitoes become infected when they feed on someone who already has the virus, and they spread it to other people through their bites.

There are other, less common ways that the Zika virus may be spread. Some of these reported modes of transmission have not been confirmed or require more research. It is not spread by respiratory droplets like SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 infection.

Mother to Child

Zika can be transmitted from a mother to her baby during pregnancy or around the time of birth.

Blood Transfusion

Through Sex

Health officials have confirmed that the Zika virus can be sexually transmitted through unprotected vaginal, anal, and oral sex. The virus remains active in semen longer than in other bodily fluids such as blood and urine.

Laboratory and Healthcare Settings

There have been some reports of Zika virus infections acquired in laboratory settings.

Animals

Duration of Zika Virus Infection

Complications of Zika Virus Infection

Although most people recover from Zika within a week, there can be serious complications related to the virus.

Pregnancy and Zika

Pregnant women should take special precautions to protect themselves, because Zika virus infection has been linked to miscarriage and birth defects.

The CDC recommends that women who are pregnant or trying to become pregnant should consider postponing travel to areas where Zika is a concern. If expectant mothers must travel, they should talk to their doctor ahead of time and come up with a strategy to prevent exposure to mosquitoes and practice safe sex.

The CDC advises men who plan to conceive not to have unprotected sex for at least three months after any possible Zika exposure or symptoms since the virus can survive in semen for a prolonged period.

Microcephaly

Related Conditions of Zika

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Several countries have reported increases in cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) following Zika outbreaks.

Other Insect-Borne Diseases

Diseases Carried by Ticks, Mosquitoes, and Fleas Triple in the US

Just as alarming as the increase in known diseases is the fact that nine new germs spread by mosquitoes and ticks have been discovered in the United States and its territories since 2004. These include the Bourbon virus, a rare and deadly tick-borne disease that was first spotted in Bourbon County, Kansas, in 2014, and the Heartland virus, which is most likely transmitted by lone star ticks and is endemic to midwestern and southern states.

Resources We Love

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

The CDC offers science-based, data-driven info on Zika in the United States and abroad, including the basics about the virus, tips on prevention and mosquito control, and up-to-date maps and statistics.

World Health Organization (WHO)

The WHO directs and coordinates international health within the United Nations. Check out their website for comprehensive coverage of Zika, including fact sheets on the virus and associated conditions, updates on outbreaks, and answers to common questions.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Diseases (NIAID)

Part of the National Institutes of Health, the NIAID undertakes and supports research into infectious, immunologic, and allergic diseases. On their website, you can find the latest news about treatment and vaccine research.

Additional reporting by Lynn Marks.

Editorial Sources and Fact-Checking

- The History of Zika Virus. World Health Organization (WHO). February 7, 2016.

- Marini G, Guzzetta G, et al. First Outbreak of Zika Virus in the Continental United States. Eurosurveillance. September 14, 2017.

- Zika: Health Effects and Risks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). May 14, 2019.

- Zika: Symptoms & Causes. Mayo Clinic. February 6, 2021.

- Zika Transmission Methods. CDC. July 24, 2019.

- Zika: Sexual Transmission & Prevention. CDC. May 21, 2019.

- Healthcare Exposure to Zika and Infection Control. CDC. December 12, 2017.

- Zika and Animals. CDC. November 15, 2018.

- Dudley DM, Van Rompay KK, et al. Miscarriage and Stillbirth Following Maternal Zika Virus Infection in Nonhuman Primates. Nature Medicine. July 2, 2018.

- Testing for Zika. CDC. January 3, 2019.

- Zika Virus Infection. BMJ Best Practice.

- Swaminathan S, et al. Fatal Zika Virus Infection With Secondary Nonsexual Transmission. New England Journal of Medicine. November 10, 2016.

- Cunha A, et al. Microcephaly Case Fatality Rate Associated With Zika Virus Infection in Brazil: Current Estimates. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. May 2017.

- Rice ME, et al. Vital Signs: Zika-Associated Birth Defects and Neurodevelopmental Abnormalities Possibly Associated With Congenital Zika Virus Infection — U.S. Territories and Freely Associated States, 2018. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. August 10, 2018.

- Zika Virus. Fact Sheet. July 20, 2018.

- Zika Virus Treatment. CDC. May 21, 2019.

- Complementary & Integrative Health Approaches. Preparing International Travelers. Chapter 2. CDC Yellow Book. CDC. June 24, 2019.

- Prevent Mosquito Bites. CDC. December 4, 2019.

- Repellents: Protection Against Mosquitoes, Ticks, and Other Arthropods. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

- Zika: Pregnant Women. CDC. April 23, 2020.

- Microcephaly Information Page. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. June 13, 2018.

- Facts About Microcephaly. CDC. October 23, 2020.

- Barreto de Araújo TV, Arraes de Alencar Ximenes R, et al. Association Between Microcephaly, Zika Virus Infection, and Other Risk Factors in Brazil: Final Report of a Case-Control Study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. March 1, 2018.

- 2018 Case Counts in the U.S. CDC. June 25, 2019.

- 2020 Case Counts in the US. Zika Virus Home. CDC. February 5, 2021.

- 2016 Case Counts in the U.S. CDC. April 24, 2019.

- WHO Statement on the First Meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee on Zika Virus and Observed Increase in Neurological Disorders and Neonatal Malformations. WHO. February 1, 2016.

- Sevvana M, Long F, et al. Refinement and Analysis of the Mature Zika Virus Cryo-EM Structure. Structure. June 26, 2018.

- Mazar J, Li Y, et al. Zika Virus as an Oncolytic Treatment of Human Neuroblastoma Cells Requires CD24. PLoS One. July 25, 2018.

- Zika and Guillain-Barré Syndrome. CDC. May 14, 2019.

- Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vector-borne Disease Cases — United States and Territories, 2004–2016. CDC. May 4, 2018.