Myasthenia gravis is a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular condition that causes muscle weakness and severe fatigue.

The term “myasthenia gravis” is Latin and Greek in origin, and means "grave muscle weakness."

The condition primarily affects the skeletal muscles, or the muscles attached to bones and responsible for skeletal movement.

As many as 60,000 Americans are living with the condition, the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America says, but the disease often goes undiagnosed. (1)

Currently, there’s no cure for myasthenia gravis. However, available treatments usually can control symptoms, allowing those diagnosed with the condition to lead relatively normal lives.

In addition, most people with myasthenia gravis have a normal life expectancy.

Causes and Risk Factors of Myasthenia Gravis

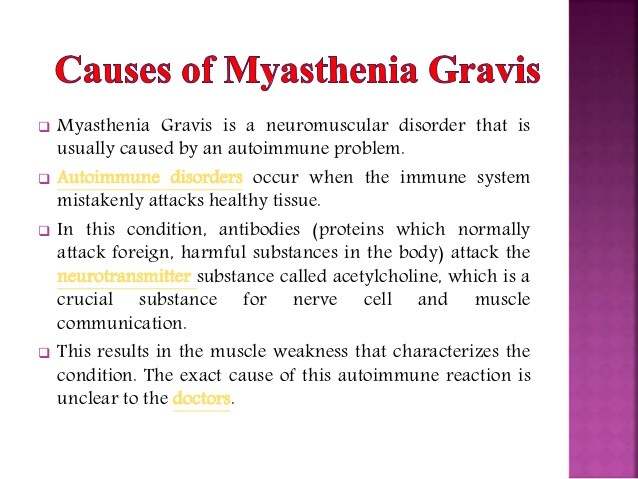

Myasthenia gravis is caused by a breakdown in the normal communication between nerves and muscles that occurs at the neuromuscular junction, where your nerve cells connect with the muscles they control. (7,8)

Normally, at the neuromuscular junction, when your brain sends electrical signals or impulses down a motor nerve, the nerve endings release a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which attaches, or binds, to sites in your muscles called acetylcholine receptors. This activates the muscle and causes a muscle contraction.

In people with myasthenia gravis, however, antibodies (proteins produced by your immune system to fight off infection) block, alter, or destroy the receptors for acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, which prevents the muscle from contracting. This is typically caused by antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor.

In addition, antibodies to a protein called muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) may also disrupt transmission at the neuromuscular junction.

Researchers also think that a part of your immune system called the thymus gland, situated in the upper chest beneath your breastbone, may trigger or maintain the production of the antibodies that block the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

While the thymus is small in healthy adults, it's abnormally large in some adults with myasthenia gravis.

In addition, tumors (which usually aren't cancerous) may be present in the thymus glands of people with myasthenia gravis, affecting antibody production. These tumors are called thymomas.

The role of antibodies and the thymus gland in myasthenia gravis in some people is what makes the condition an autoimmune disorder — meaning that the immune system mistakenly attacks itself.

However, some people have what’s called antibody-negative myasthenia gravis, which means the condition hasn’t been caused by antibodies blocking acetylcholine or MuSK. In these cases, antibodies against another protein, lipoprotein-related protein 4, play a part in the development of the condition.

In addition, in rare instances, mothers with myasthenia gravis have children who are born with the condition because they pass antibodies blocking acetylcholine or MuSK to the fetus in the womb. This is called neonatal myasthenia gravis.

However, if the condition is diagnosed and treated promptly, these children generally recover within two months of their birth.

Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome

Some children may also be born with a rare form of myasthenia gravis called congenital myasthenic syndrome. (9)

The condition is extremely rare, and unlike myasthenia gravis, congenital myasthenic syndrome is not an autoimmune disease. Instead, it’s caused by inherited genetic mutations of the CHRNE, RAPSN, CHAT, COLQ, or DOK7 gene.

Like people with myasthenia gravis, children with congenital myasthenic syndrome experience muscle weakness (myasthenia) that worsens with physical activity. This typically begins in early childhood but can also appear in adolescence or adulthood.

The muscles in the face, including those that control the eyelids, move the eyes, and enable chewing and swallowing, are most commonly affected. However, other skeletal muscles can also be affected.

Because of the muscle weakness caused by congenital myasthenic syndrome, infants may have feeding difficulties and may experience delays in their development of motor skills, including crawling or walking.

Myasthenia Gravis and COVID-19

In August 2020, researchers in Italy described the development of myasthenia gravis in three adults with severe COVID-19 in an article published in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine. (10)

The three adults, who ranged in age from 64 to 71, developed their myasthenia gravis symptoms five to seven days after fever related to the new coronavirus first appeared. None of the three had prior history of neurologic or autoimmune disorders.

However, all three were positive for antibodies that block acetylcholine. These antibodies, which have been shown to cause myasthenia gravis, may have been activated by COVID-19, the researchers say.

One of the three developed respiratory failure — either as a result of the virus or myasthenia gravis.

Although the potential links between COVID-19 and myasthenia gravis are concerning, as infections continue to rise globally, it’s important to note that these are the only three cases to have been reported so far.

Still, if you have myasthenia gravis, it may place you at increased risk for serious illness from COVID-19. Talk to your doctor about steps you can take to minimize your risk.

Duration of Myasthenia Gravis

Even if your myasthenia gravis goes into remission, it can still return. Indeed, once you’ve been diagnosed with the condition, you’ll likely be managing its symptoms for the rest of your life.

Complications of Myasthenia Gravis

While complications of myasthenia gravis are treatable, some can be life-threatening.

Complications may include the following:

- Myasthenic crisis is a life-threatening condition that affects breathing and requires immediate treatment for the person to be able to breathe on their own.

- People with myasthenia gravis may also experience more severe symptoms from high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease than others. (17)

- Thymus tumors, which usually are not cancerous, occur in about 10 percent of people with myasthenia gravis, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). (7)

- People with myasthenia gravis are more likely to have underactive or overactive thyroid and autoimmune conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus. (17)

BIPOC Communities and Myasthenia Gravis

Research on myasthenia gravis in BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities is lacking. However, one small study found that the condition seems to develop earlier — or at a younger age — in African Americans than in white Americans. (18)

That same study also suggests that the incidence of AChR-Ab-positive myasthenia gravis is similar in white Americans and African Americans (71 percent vs. 59 percent), while MuSK-antibody positive myasthenia gravis is more common among African Americans than white Americans (14 percent vs. 4 percent). (18)

However, a second small study that included Hispanic and Asian participants in addition to white and African American subjects found MuSK-antibody positive myasthenia gravis only among Hispanic and Asian subjects, not in any of the white or African American subjects. (19)

Resources We Love

Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America

The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America was founded to help create “a world without myasthenia gravis.” On its website, you’ll find information pertaining to myasthenia gravis, including treatments, diagnosis, drugs, and related disorders; a Community & Resources section, where you can sign up for virtual events and support groups; and the latest in myasthenia gravis research, including information on signing up for clinical trials. It also offers an app, MyMG, which allows you to track your symptoms, record any changes in treatment or medication, and easily share this information with your doctor.

MGWalk.org

MG Walks is an initiative launched by the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, whereby annual community walks are organized to fundraise for research into the condition. While the COVID-19 outbreak has placed plans for in-person MG Walks on hold, the website continues to encourage fundraising efforts and has organized pandemic-friendly virtual events.

National Organization for Rare Disorders

The website of the National Organization for Rare Disorders is host to a wealth of information relating to myasthenia gravis. From causes and symptoms to diagnosis and treatment, this page takes a thoroughly detailed dive into the condition. Here, you’ll also find information on clinical trials in both the United States and Europe, along with a list of organizations that can offer help for people living with myasthenia gravis.

The Genetic Alliance

The Genetic Alliance is a nonprofit organization that aims to support and empower those living with genetic diseases through advocacy and education. On its website, you’ll find information pertaining to its advocacy work, as well as a Disease InfoSearch tool with an encyclopedia of genetic diseases and a Find Support page that lists over 800 disease support organizations. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Genetic Alliance has also launched Fight to End COVID, a program that is seeking people to share their experiences of living through the pandemic with a genetic disease via an online questionnaire.

Additional reporting by Brian P. Dunleavy.

Editorial Sources and Fact-Checking

- MG Facts. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America.

- Myasthenia Gravis: Symptoms & Causes. Mayo Clinic. May 23, 2019.

- MG Management. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America.

- Sanders DB, Wolge GI, Benatar M, et al. International Consensus Guidance for Management of Myasthenia Gravis. Neurology. July 26, 2016.

- Wendell LC, Levine JM. Myasthenic Crisis. The Neurohospitalist. January 2011.

- MG Crisis. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America.

- Rare Disease Database: Myasthenia Gravis. National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2017.

- Myasthenia Gravis Fact Sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. April 27, 2020.

- Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome. Medline Plus.

- Restivo DA, Centonze D, Alesina A, et al. Myasthenia Gravis Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Myasthenia Gravis (MG): Diagnosis. Muscular Dystrophy Association.

- Naji A, Owens ML. Edrophonium. StatPearls. April 30, 2020.

- Aydin Y, Ulas AB, Mutlu V, et al. Thymectomy in Myasthenia Gravis. The Eurasian Journal of Medicine. February 2017.

- Myasthenia Gravis (MG): Medical Management. Muscular Dystrophy Association.

- Myasthenia Gravis: Diagnosis & Treatment. Mayo Clinic. May 23, 2019.

- Wellness Strategies. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America.

- Tanovska N, Novotni G, Sazdova-Burneska S, et al. Myasthenia Gravis and Associated Diseases. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. March 5, 2018.

- Oh SJ, Morgan MB, Lu L, et al. Racial Differences in Myasthenia Gravis in Alabama. Muscle Nerve. March 2009.

- Abukhalil F, Mehta B, Saito E, et al. Gender and Ethnicity Based Differences in Clinical and Laboratory Features of Myasthenia Gravis. Autoimmune Diseases. June 14, 2015.